Cities, SI Urban 1/2024

Interview: Learnings from India

About 350 cable car projects have been submitted for review to the Indian state infrastructure company National Highway Logistics Management Limited (NHLML), many of which are in urban areas.

The planning office SALZMANN INGENIEURE, together with the engineers of the BERNARD Group, is examining which of these ideas make sense – and is further planning feasible projects.

Managing Director Stephan Salzmann in the SI Urban interview about the current projects “Varanasi 2“ and “Kamakhya“ – and which learnings are relevant worldwide.

SI Urban: Mr. Salzmann, one of your tasks for NHLML is the so-called Prefeasibility Studies. What can we imagine by that – and why are they so important?

Stephan Salzmann: Plans for urban cable cars from all Indian states usually come from a party or an initiative to address a specific transportation problem. Often it‘s just an idea, sometimes just two place names. We assess whether the project makes sense in general and whether a classic feasibility study is justified at all.

Therefore, we have developed a requirement profile for urban cable cars. Here, our experience from over 50 years of cable car planning, over 250 implemented cable cars, and around 150 feasibility studies helps.

For the preliminary study, we inspect the starting and ending points as well as the planned route on-site: Is the cable car technically feasible and also sensible? Are the necessary plots of land available?

Do the stakeholders – in India, for example, the army, the railway, the temple management, the conservation authority, and local actors – generally agree with the idea? Also crucial is determining the cable car‘s capacity in relation to demand.

Our partners – the engineers of the Bernard Group – calculate how many passengers would use the cable car. We, in turn, examine which cable car system would be feasible to meet the required capacity.

Showcase Varanasi

The cable car Varanasi 1 (red line) is currently under construction. Varanasi 2 (green line) is planned to be tendered later this year.

Would this approach also be advisable for Europe?

Yes, because urban cable car plans are often publicly communicated unprepared there. Arguments are not prepared in advance for the subsequent, mostly unfounded reservations. To recapture the discussion, a feasibility study is often commissioned.

But it comes too early! Our experience shows that the fundamentals for a meaningful investigation are often not available. The result of the feasibility study is then unusable and can be easily attacked by opponents. The creator can‘t help it; the groundwork is missing, similar to what we do in the aforementioned Prefeasibility Studies.

Showcase Varanasi

The Namo Ghat, a religious bathing spot, is the destination of the second urban cable car line in Varanasi.

Back to India: What follows after the preliminary study?

If we – and NHLML – generally consider a project to be meaningful, we start with the “Request for Proposal“. This phase includes the classic feasibility study, laser scanning survey, and preparation of the tender documents.

In India, a contractor usually applies, who then finds a cable car manufacturer, builds the cable car, and operates it for at least five years. Afterwards, NHLML buys back the cable car at an agreed price. The construction is supervised by an Applied Engineer.

A prime example of this would be Varanasi?

Yes, the cable car plans in the major pilgrimage city on the Ganges are certainly groundbreaking. The first line Varanasi 1 is already under construction. The single-cable ropeway with 10-person cabins will soon run from Varanasi Cantt station through Vidya Peeth and Rath Yatra stations to the Godowlia Chowk temple district.

For the second line Varanasi 2, we are currently finalizing the route, and we still have to consider at least two more cable car lines planned for the future. Varanasi 2 starts at the bus station of Cantt station – so in the vicinity of Varanasi 1 – and leads through four intermediate stations to Namo Ghat, a religious

bathing spot on the Ganges.

On its way, the cable car connects a university, an industrial area, and Varanasi City Station. The capacity of the approximately five kilometer long cable car will likely be around 3,000 passengers per hour and direction.

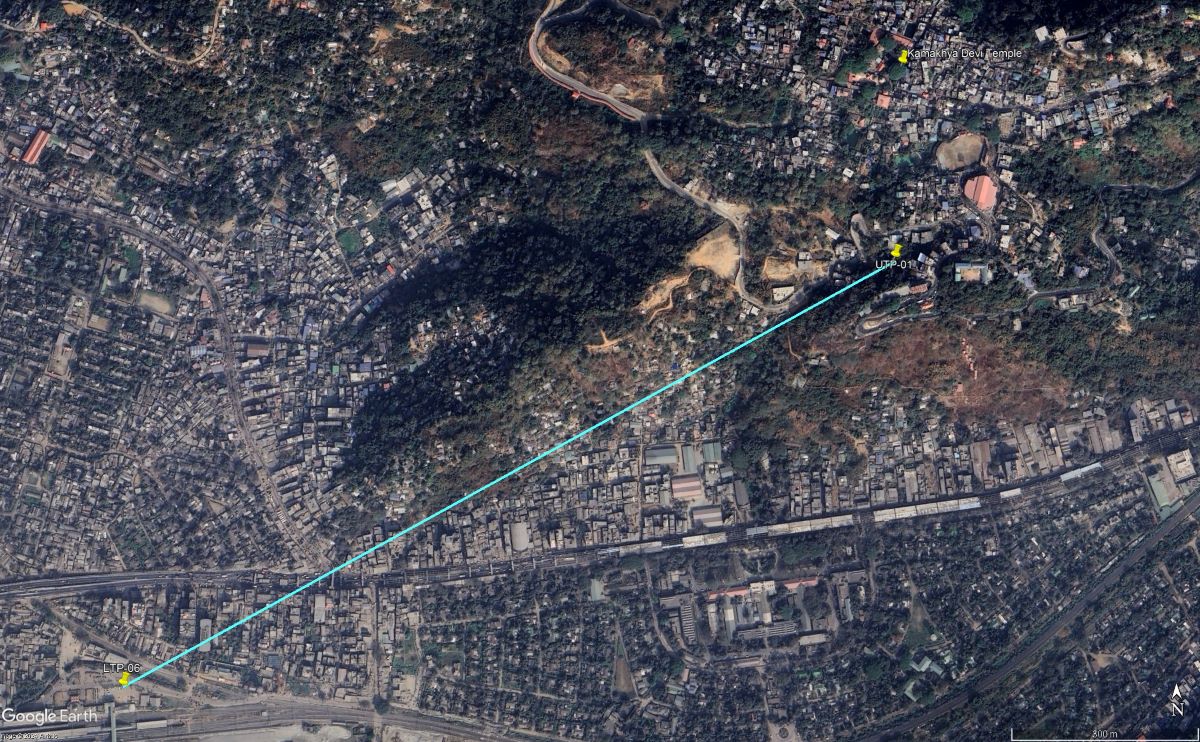

The Kamakhya temple district

in Guwahati is the destination of

many pilgrims.

What challenges are there in Varanasi – and are they transferable to other parts of the world?

In India, only public land can be used for stations and supports. These must be available in advance and cannot be acquired during the project process. This is not the case in other countries.

In Varanasi, therefore, some supports are on roads. Table constructions are necessary here, under which traffic can pass through. This can in turn be a global model if there are tight space conditions.

In addition, we must evaluate fire hazards in Varanasi and avoid overhead lines – this is also transferable worldwide. And early stakeholder involvement is certainly a success factor in other countries as well, for urban cable cars to succeed.

One difference between India and Europe, for example, is the crossing rights. In Varanasi, we can pass over properties with cables and vehicles without having to obtain the consent of the owners and residents. However, the population welcomes the relief provided by the cable car anyway.

The cable car in Guwahati

is intended to connect the railway station to the Kamakhya temple district and transport 800 people per hour.

What role does tourism play in urban cable cars?

The main purpose of Varanasi 2 is – in addition to the locals – to transport pilgrims and tourists. We are talking about several hundred thousand visitors daily in Varanasi overall!

With the ride over the rooftops of the city, the cable car is inherently an attraction, but at the same time supports visitor management to relieve other religious bathing spots. Varanasi 2 is thus a hybrid system of urban and tourist use. There are, of course, purely urban-touristic cable car plans as well.

Currently, we are working on a cable car in Guwahati, Assam. Here, the Kamakhya temple district is to be developed. So far, people only reach the mountain on foot or by cumbersome car ride. The cable car is intended to provide a fast and comfortable alternative here.

The valley station will be positioned directly next to the railway station so that pilgrims and tourists can board the cable car directly from the train. Of course, the dimensions are smaller for such a project: here we are talking about a capacity of 800 people per hour and direction with a track length of 1.7 kilometers. Such a system can be implemented worldwide!