Cities, SI Urban 2/2022

More acceptance for urban cable cars

Ulrich Arndt, Head of the Department for Civil Society and Citizen Participation of the German state of Baden-Württemberg, showed at the Cable Car World Congress how this is done and which instruments authorities and politics can use.

Dialogue-based citizen participation is necessary for urban cable car plans to be accepted by the population, Ulrich Arndt is convinced.

In contrast to direct democracy, in which the voters decide for themselves, in dialogical citizen participation, authorities and parliaments continue to determine the outcome of a project; however, citizens have a say beforehand.

“The example of the Brexit shows us that citizen participation is the better way,” says Arndt in his presentation at the Cable Car World congress fair.

Dialogue-based citizen participation is not to be confused with public participation, Arndt emphasised:

“Public participation requires being affected and having an interest of one’s own and is purely a hearing. Dialogue-based public participation, on the other hand, does not require concern and serves to form opinions!”

Danger of escalation

If the population is involved late or not at all in urban cableway projects, there is a risk – as with probably every infrastructure project – of an escalation of the political debate and an explosion of costs.

“With early public participation, unrest is created immediately, but afterwards the excitement curve drops because the discussion is differentiated and the cost development can be controlled,” says Arndt. He was able to identify five essential experiences and patterns:

Ulrich Arndt

Ulrich Arndt

Head of the Office for Civil Society and Citizen Participation in Baden-Württemberg

Ulrich Arndt is head of the staff unit of the State Councillor for Civil Society and Citizen Participation at the Ministry of State of Baden-Württemberg. Since 2011, the federal state has placed a focus on citizen participation with Prime Minister Kretschmann’s “policy of being heard”. Together with close scientific support, it was possible to massively expand citizen participation in Baden-Württemberg.

1. Create options for action

First of all, civic participation requires room for manoeuvre; just informing is not enough. “The term ‘Alternativlos’ (without alternatives) has already been the German ‘Unword of the Year’,” Arndt puts it succinctly.

If, on the other hand, options for action are created – for example by engineers involved in the project – the population’s perception of risk is reduced.

“But never start the debate with expert findings and do not announce milestones in the process,” Arndt recommends.

Random citizens

counteract the “false balance” in the debate. Photo: State of Baden-Württemberg

2. Hidden motives

A major problem in the discussion about infrastructure projects are the hidden motives of those involved.

For example, nature conservation is often used as an excuse, although the fear of change is the actual driving force.

“The four classics are property values, health concerns, the landscape and historical precedence,” says Arndt. It is therefore essential to avoid sideshows with battles between experts.

3. Communication

The project and the procedure must be communicated in an appropriately considered manner. Arndt has identified four success factors. Firstly, a sensitive handling of “big terms”.

“Rather speak of the new building of Hall 10 than of a major project,” Arndt gives an example.

Secondly, citizen participation should be concrete and focus on contentious issues. Only then is it relevant.

Thirdly, the “false balance” should be reigned in, i.e. excessive media coverage in favour of citizens’ initiatives.

“Citizens’ forums with randomly selected participants can help to achieve a more balanced opinion in the media,” says Arndt.

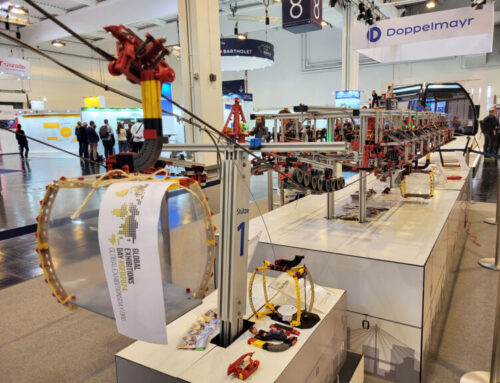

Fourthly, graphics of the planned project are essential. Correct renderings eliminate the horror pictures of the citizens’ initiatives – for example of oversized supports and huge cable car stations.

Photo: DOPPELMAYR

4. Actors

As an actor analysis revealed, the biggest “opponents” of dialogue-based citizen participation are often citizens’ initiatives and environmental associations.

The reason is their understanding of their role as a “jury”; their lobbying serves as their raison d’être.

“Dialogue-based citizen participation relativises their previously highlighted position in the media – of course, citizens’ initiatives and environmental associations don’t like that,” says Arndt.

Random citizens take their place. Those selected by lot increase the proportion of women, young people, migrants and silent groups.

“So people enter the discussion who are not involved in the previous dispute – and not just the particularly committed men over 60,” Arndt explains with a grin.

The random citizens complement the already set organised actors, they have a de-escalating effect and put the claim of the “common good” by individual actors into perspective.

New ideas – not “the usual ones” – thus flow into the debate, the supposed distance between the people and politics as well as the false balance are overcome. Video conferencing helps to lower the threshold for participation.

5. Responsiveness

Dialogic citizen participation acts as a resonance chamber, with it accountability can be given and responses can be voted on.

“Maybe the result – for example the construction of a cable car – is not accepted by some. But they agree with the process that has taken place up to that point,” says Arndt.

The decisive factor here is the ability of politicians and authorities to respond. It is the other side of being heard; communication takes the place of announcement.

“Let them see you, talk to them on the phone and listen to them. Paraphrase their concerns in letters and give input-oriented, friendly answers.”