Cities, SI Urban 1/2020

FLYING HIGH – OR MAYBE NOT?

Maike Puhe

Qualified geographer and – since 2010 – member of academic staff at ITAS (Institute for Technology Assessment and Systems Analysis) in Karlsruhe. Her focus lies in the area of mobility research, on which she has already published a number of studies, including – together with her colleague Max Reichenbach – the study “Flying high – On the feasibility, opportunities and obstacles for urban cable cars in Baden-Württemberg”.

In Germany there are a few projects to date in which the question remains, whether this is really public transport in the traditional sense. Puhe points out: “Among the population in particular, consideration is given to whether it is used as a daily means of transport on the way to work and school.

The familiar example of the Koblenz cable car is irrelevant for commuter movement; rather, it serves as a point-to-point connection for tourists and many people do not regard it as an extension of the public transport provision.”

Image

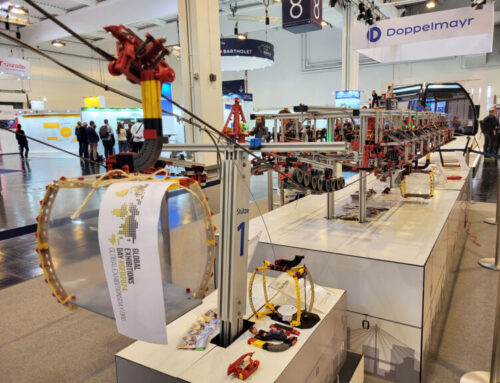

Cable cars are very eco-friendly to operate, can easily be fitted with solar panels and have been powered by electricity for many years. These factors are a perfect match for the present development of mobility. Cable cars have therefore become an opportunity to improve image among certain target groups and to attract attention.

Meanwhile, the wind is blowing from another direction and attempts are being made to evaluate cable cars open-mindedly and not as an image factor. As the present showcase projects are located outside Europe, however, the data required for processing through planning are frequently lacking.

The sky in private ownership

Cable cars do score points for their low construction cost, as only the supports and stations are located on the ground, but the routing is not easy to implement in an urban area. In German law, air space above private property also belongs to the owner, such that, before construction begins, many individual solutions would have to be found for the individual properties to be flown over.

In other countries, such as Bolivia, the legal position makes the construction of such a means of transport significantly easier. However, the legal position is difficult not only in terms of route planning; there is an almost insurmountable obstacle to a cable car even in the planning process.

One of the greatest barriers lies in standardised valuation. In this process, the practicability of potential transport systems is examined. A feasibility study is naturally also possible for cable-drawn systems but standardised valuation often becomes a problem here.

Whereas any cost valuations for buses, trams and trains have been collected over decades, such figures are unavailable for these ascent aids. Cable cars have proven over decades that they are suitable for use as tourist attractions but the demands of an urban mode of transport are different.

Part of the standardised cost-benefit analysis is also a simulation and whereas the paternoster principle of cable cars in more normal capacity use is easy to simulate, there is a lack of empirical values for waiting times during peak periods, for example if passengers of a full tram have to be transported further.

This chicken- and-egg problem will continue to occupy planners for some time, as all these data would be easy to collect if such a cable car were constructed in Germany but submission of the standardised valuation is impossible without these data, which is a requirement for a public sector subsidy.

Study conclusion

So that an urban cable car can be constructed as a part of the public transport in Germany, the study envisages a number of necessary steps: “The most important would be a showcase project in Germany at some point although, regardless of this, uncertainties in the population would also have to be resolved.

Furthermore, an analysis of the necessary requirements for a cable car project should also be conducted before the public announcement. In the final stage, the statutory framework conditions would have to be adjusted; at present, each of the 16 federal states has more or less individual legislation concerning the integration of cable cars,” Puhe briefly summarises the study results.

An urban cable car remains a fine application example of a technically fully developed and proven system, which has not yet seen a complete victory in urban areas, owing to various obstacles. However, this could change in the coming years.