Cities, SI Urban 1/2022, Tourism

Interview – “THE FEASIBILITY STUDY OFTEN COMES TOO EARLY”

SI Urban: Mr Salzmann, why do many urban cable car projects fail even in the early stages?

Stephan Salzmann: Ideas for urban cable cars generally come from a party or from an initiative for a specific transport problem. Plans are tossed to the public unprepared; no arguments are established in advance to counter familiar, generally unfounded reservations.

A feasibility study is often commissioned, in order to restart the discussion. The instigators think that they are doing the right thing here, but they are actually doing precisely the wrong thing.

In what respect?

The feasibility study often comes too early. Our experience has shown that the basis for a meaningful investigation is usually not in place. The result of the feasibility study is then unusable and easy for opponents to attack. That is not the fault of the author: the groundwork is missing.

What should the people responsible do instead?

Politicians, town planners and instigators should start by identifying the mobility needs of their communities – regardless of the specific transport problem for which they envisage a cable car solution.

On the one hand, this concerns the status quo: at which locations in the city are there mobility problems, such as congestion, poor public transport connections or long waiting times?

On the other hand, the future needs to be taken into account: how will the city develop in the next few years? Where are new settlements, institutions or commercial areas emerging, which need to be connected to the public transport network? This requirement analysis must be compiled in advance, without a cable car even being an issue.

Which questions need to be resolved even before a feasibility study is conducted?

On the basis of the mobility needs, the people responsible need to define which requirements the new public transport has to meet. We are talking about transport capacity, operating hours and terms of use here.

Does it have to be able to transport pushchairs, bikes or e-scooters? Even at this stage, it may emerge that a cable car is not appropriate and no feasibility study is needed. For example, with a brief analysis for one community in Germany, we clarified within two days whether a cable car is actually appropriate.

Because the costs of such initial clarification are manageable, amounting to between one and three days’ work, commissioning is usually possible quickly and unbureaucratically.

What specifically do you do here?

We have developed a requirement profile for urban cable cars, with which the fundamental sense of the ideas can be verified even before a feasibility study is conducted. This then also helps us as cable car planners and manufacturers, since the industry gains nothing from feasibility studies that fail. Every cable car project that is publicly abandoned has an adverse effect on other cable car ideas, as the sceptics regard it as confirmation of their fundamental rejection.

In general, communication seems to be key. How and when should the public be informed?

The sooner the better. At the latest, the cat will be out of the bag with the call for tenders for the feasibility study, and there is a high risk of the project being abandoned. This is why the public needs to be involved right from the stage of the requirement analysis, which is conducted regardless of the mode of transport.

Public involvement, e.g. in the form of a future workshop, has proven successful here, with the questions for the feasibility study being formulated collectively, which increases acceptance of the results.

The local transport companies need to be involved here, as potential operators. Furthermore, the public participation process takes the wind out of the sails of those sceptics who come across the plan only later on. In the workshops, they would have been able to contribute their questions, fears and criticisms of the cable car, even before the feasibility study.

Can you give some examples here?

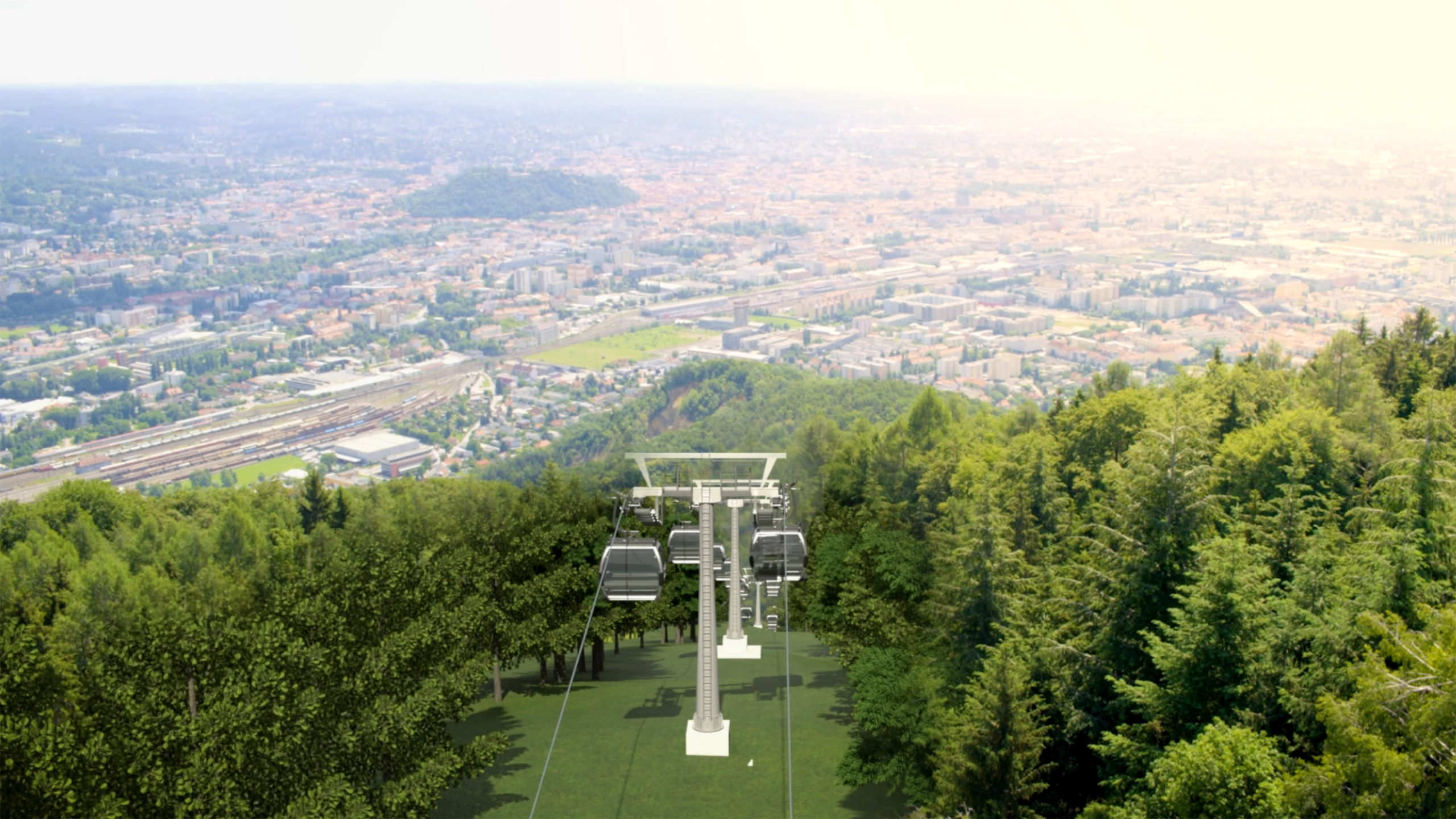

Most of the arguments are familiar and easy to refute. On the issues of wind and noise, many people connect urban cable cars with their experience in the mountains, and they envisage problems with operating safety. Here, wind is rarely a problem in cities, and the noise on Alpine cable cars generally comes not from the installations themselves but rather from the surroundings. The issue of privacy can be tackled with tinted windows and with routes that run only over undeveloped or public land. At the moment, it is generally still hard to imagine cable cars in Europe that would operate over built-up areas.

If the people responsible now opt for a feasibility study, what should they bear in mind?

The references of the bidders should be defined according to their specialisations. Practical experience with cable cars would be important to me as a client, as practical knowledge from the construction and operation of a cable car is relevant for proper assessment of the effects. Involving executing businesses such as cable car manufacturers at the feasibility study stage will inevitably result in conflicts of interest and incompatibilities under the current awarding rules, so I recommend commissioning an independent cable car planner.

Which points should a feasibility study cover?

Initially, a study of the options, including all modes of transport and routes in consideration, on the basis of the issues previously identified: are they eligible for approval as well as economically viable to construct and operate?

A rough plan and a cost estimate are needed here. Sometimes the eligibility emerges even at this point. Then the options undergo standardised assessment, particularly in respect of integration into the urban landscape and the public transport network.

The potential construction and operation phase is also included in this: how severely will installation adversely affect city life and is cable pulling possible several times?

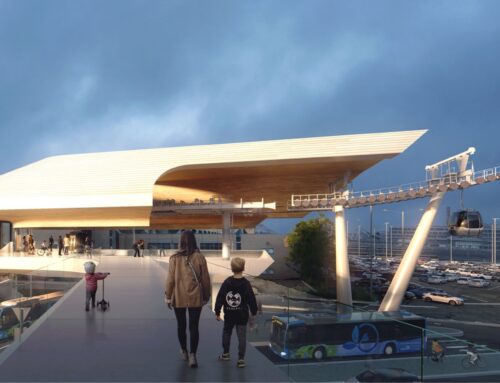

The architecture is also considered at this stage, and illustrations of stations and routes are produced, because realistic visualisation is immensely important for communication. Economising on the pictures will quickly result in horror graphics from the opposition, which will be impossible to get out of people’s minds.

About Salzmann Ingenieure ZT GmbH engineers

Salzmann engineers, based in the Austrian city of Bregenz, have 50 years of experience in the planning and implementation of cable cars. The experts have implemented over 200 projects to date, as well as over 150 feasibility studies and consulting projects.

SALZMANN maintains close links with manufacturers, suppliers and authorities. Moreover, the company contributes to fundamental research into cable cars and has developed a requirement profile for urban projects. Contact details and information: salzmann-ing.at.