Cities, SI World 2/2019

Urban cable cars: The perfect solution! But to what?

If you look at the reporting in European media, the system in the Bolivian capital La Paz is cited most frequently as a reference in connection with urban cable car solutions. It has been clearly proven there that urban cable cars can be mainstays of innercity public transport systems.

Although the efficiency and significance of the solution in La Paz are not in question, critical scrutiny is required concerning the circumstances in which comparison with other cities is meaningful.

For German cities alone, well over twenty studies into urban cable car systems have been produced in the past but only few, such as the one in Koblenz which must be classed more as a tourist attraction than as urban transport, have actually been constructed. So why are solutions from Latin America not used in Europe?

From why to how

To put the comparison with cable car systems in other cities into perspective, it is worth taking a look behind supposed solutions, at the underlying

problems. When considered like this, the more specifically a problem or need is formulated, the easier it is to determine the solution.

This sounds simple but often proves to be a fundamental stumbling block in project development, as it is not uncommon for needs and solutions to be confused. It is then up to the solution provider to identify the actual needs and define the optimal solution. In this case, the approach of a transport solution provider is similar to that of a DIY product supplier.

In a DIY store, if you to buy the right tool for a project, you should describe what you want to achieve and not what you want to have. Rather than asking for a diamond drill, you should tell the trained salesperson that you want to drill through a tile to attach a hook.

When the adviser knows what the customer needs, the optimal solution can be offered, for example a hook stuck onto the tile rather than a hole drilled in the tile. Several lines of thought for planning transport solutions can be derived from this comparison:

1. Every town should approach the specific mobility needs of the population with a mind that is open to solutions. To do this, it needs partners who

consider the complete spectrum of urban mobility solutions and regard cable cars as one option in an overall, intermodal solution.

2. For sustainable planning of transport solutions, the present situation must be extrapolated into a future scenario. Otherwise, at best, existing problems will

be solved without ensuring that potential future problems are considered.

Looking to the future, current transport data are reconciled with urban planning concepts and demographic developments. A four-dimensional image of the city needs to be compiled.

3. Comparison with other cities usually yields no enlightening insights for the challenges of the focus city. Looking at these aspects, we see that many feasibility studies concentrate more on “how” than “why”. Almost anything is technically feasible today.

Many things can also be financed if cities are willing to create appropriate framework conditions. On the question of which set of measures is suitable to meet the mobility needs of the respective city in the long term, the answer in a sophisticated urban environment may be to defuse hotspots and among other things to take a new approach with regard to neighbourhood formation and commuter behaviour.

The fact that cable cars can play a pioneering role in both cases has now been adequately proven.

There are over 20 urban cable car studies in

Germany but only a few have been

implemented, such as here in Koblenz.

Photos: DOPPELMAYR

From group to individual

Any solution approach, no matter how comprehensive its conception or how long-term its planning, can fail if communication with the groups of people affected is inadequate. Inadequate does not mean a lack of communication but rather the inability to communicate the many individual advantages of the project measure so that they are recognisable.

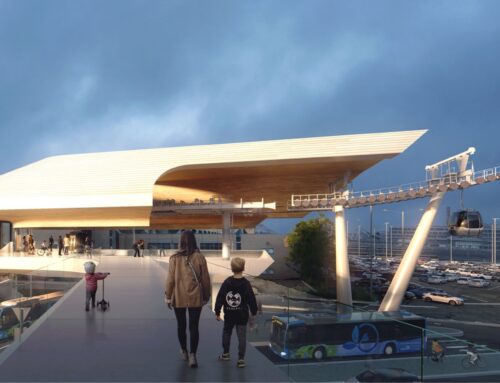

It is relatively easy to address the superficially uniform group of neighbours of a planned cable car station with regard to potential strains during the construction phase. However, differentiated consideration of the group of neighbours is required when it comes to the effects of the new mobility provider, e.g. such as rising pedestrian numbers.

How will the parking situation change? How will residential or business rents increase etc.? The assessment and representation of the individual benefit will vary and need to be addressed differently depending on the personal situation.

It is therefore not only representation of the sense of the project that is crucial for acceptance of urban mobility solutions but also the ability of the project developer to communicate the motives and objectives of the project.Why are we doing it?

Which problems do we want to solve? According to which criteria will we decide? Professional project communication that is planned from the outset and actively pursued is therefore not merely a secondary element in order to comply with directives but rather essential to guarantee the success of the project.

From narrow to holistic view

One of the key questions of feasibility studies is: “when does a project become worthwhile?” Put simply, passenger numbers, ticket prices and operating costs are analysed here over long periods and compared with the investment costs in discounted form.

However, if e.g. a country such as Luxembourg decides to provide public transport free of charge in the future, on social grounds and based on integration and environmental policy considerations, it quickly becomes apparent that business case decisions are not based solely on direct financial return on investment.

As the organiser of numerous conferences, Luxembourg now profits from the indirect benefit of efficient public connections, as this contributes to increased appeal of the conference location. Such additional revenue generated must be examined accordingly and subsequently taken into account in decision-making processes.

Today, the cost-benefit calculation of public transport measures must therefore deliver considerably more than can be represented by capacity and use, line layout, station planning and intermodal connections.

Consulting companies and planning experts must now analyse mobility needs in way that is open to solutions, examine urban development concepts (increasingly taking into account growing commuting radii) holistically and demonstrate the many individual advantages, in order to develop the optimal solution combination.

It is only from this holistic and multidisciplinary perspective that the potential of cable car systems can also be fully exploited in the sophisticated urban environment.