Cities, SI Urban 1/2020

SOCIAL CABLE CAR

To meet the demands of public transport, cable cars must fulfil the requirement of general accessibility. Frieder Kremer has demonstrated what this means in his book, “Innovation Seilbahn” (Innovation Cable Car). The following is an extract from his publication, with a few editorial amendments (TU Berlin [Berlin Institute of Technology] 2015: pp. 47-48.

Barrier-free – that‘s what cable cars should be – and they are.

Essentially, all groups of people and all age groups – regardless of physical or other limitations – must be able to make full use of cable cars. Greater demands are therefore placed on their safety, ease of use and above all accessibility.

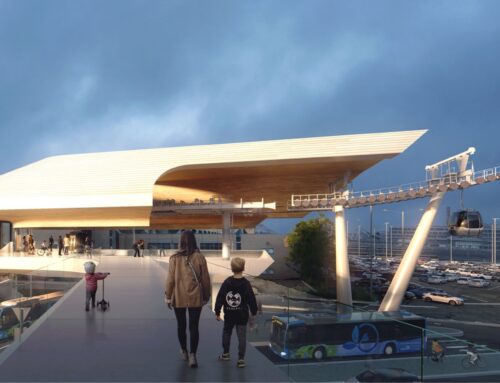

Accessibility is created with level installation of stations or the provision of access to a higher entrance level by opening up the inside of the station (e.g. using lifts and ramps). As the individual gondolas are conveyed only at low speed inside the station, boarding and alighting are manageable with no major problems, even for people with limited physical ability. Photos: DOPPELMAYR

If necessary, the gondolas can even be stopped completely and boarding can take place when stationary. Furthermore, bulky items (e.g. wheelchairs, pushchairs, bicycles) can also be taken in the gondolas with no problem.

Issue of claustrophobia

However, accessibility is more difficult for people with psychological barriers, such as acrophobia or claustrophobia. As cable cars have a relatively small vehicle size and the movement takes place in the air, these anxieties are intensified further in comparison with conventional modes of transport.

It therefore seems sensible to provide an alternative transport system (e.g. a bus service) for those users who are unable to use cable cars as a means of transport, owing to psychological or physical limitations.

However, as these anxieties (especially claustrophobia) can equally occur in the case of underground railways and other conventional modes of transport, the operation of an alternative system does not represent an essential prerequisite for approval of a cable car system.

As such, this aspect illustrates that the significance of the psychological barriers is also always dependent upon the level of familiarity with the type of movement.

Social participation

Social conflicts

In addition to the many advantages that cable cars bring by virtue of their own route, they also create social conflict as a result: the elevated travel position allows views into the privacy of residents.

This must be taken into account and minimised as far as possible right from the route planning and system design. The acceptance of a cable car system within the public transport infrastructure is reflected in the number of users. It therefore represents an important indicator of the success of the respective system.